Floods remake the landscape, altering the course of rivers and gouging valleys out of the earth. They also inundate our dreams. For thousands of years, torrential waters have shaped our collective imagination with indelible force. Apocalyptic storms and violent swells that submerge the land and claim the lives of all but a few survivors appear in the ancient myths of cultures around the world. From Australia to Alaska, Transylvania to Tahiti, floods have been agents of divine wrath, reminders of human weakness, and catalysts for planetary renewal.

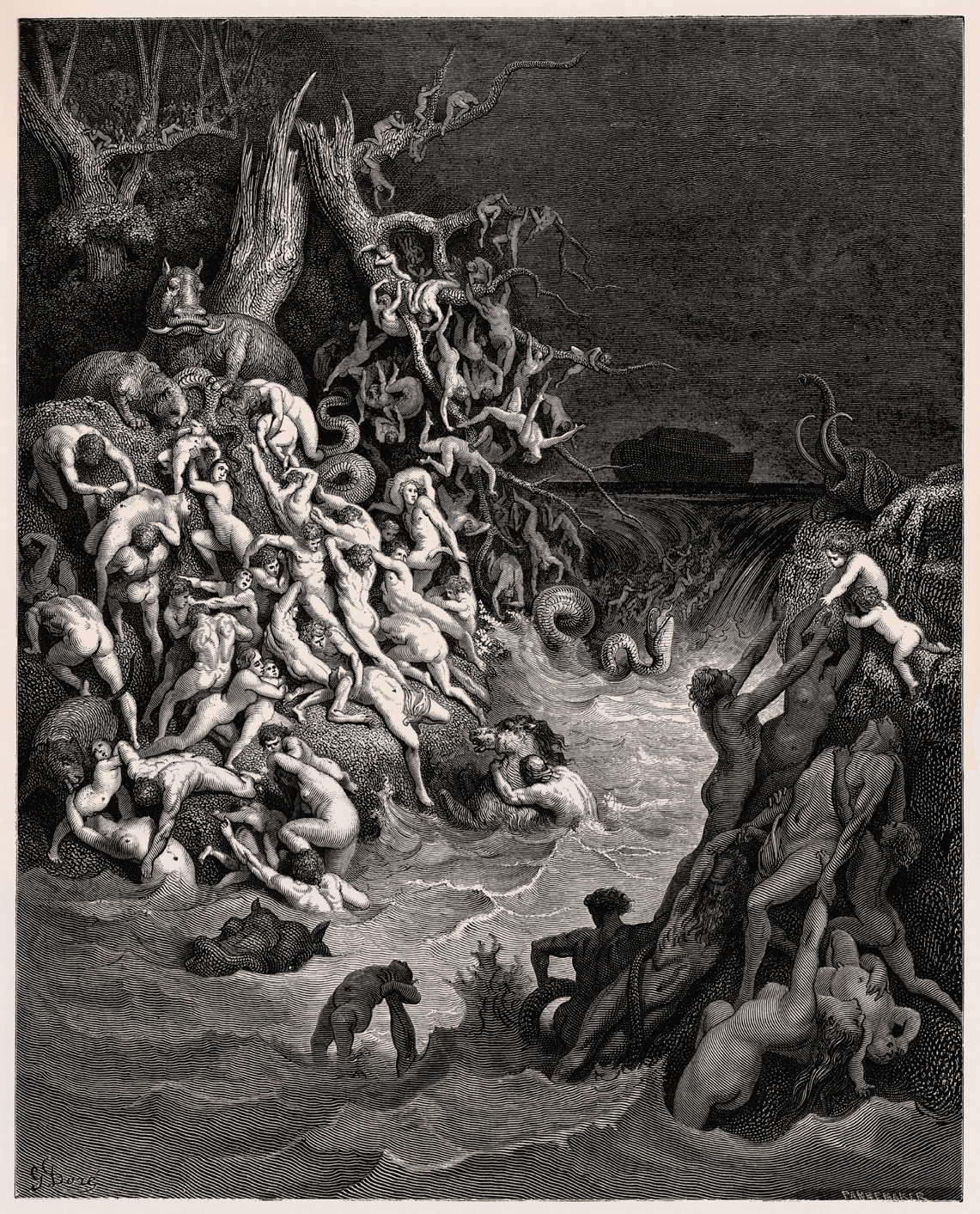

Of these floods, none has inspired as many works of art as the Deluge described in Genesis. The watery disaster has remained one of the most popular subjects in Christian art since the third century, when the faithful first painted Noah bobbing helplessly in a wooden box on the walls of the Roman catacombs. Over time, artists shifted their focus from the flood’s pious survivor to its anonymous victims. By the Renaissance, painters were using the Deluge to plumb the psychological experience mass of panic and desperation: Paolo Uccello depicted two men, waist deep in water, attacking each other in a fresco for Santa Maria Novella in Florence. On the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo painted a trail of refugees carrying the injured and a few possessions—some bread, a skillet, a stool—while a few frantic men attempt to break into the ark floating serenely in the distance. The most nightmarish depiction of the Deluge might be The World Destroyed by Water, an engraving from 1866 by the French artist Gustave Doré. Terrified humans, elephants, hippos, and snakes scramble up steep cliffs to escape torrents of rushing water. A single arm emerging from the surf holds an infant above the waves.